Setting the Flight Endurance World Record

There are a lot of world records related to flight. They can be in either a manned or unmanned aircraft, re-fueled or un-refueled, and cover areas such as flight distance, speed, or altitude. One of the most interesting and sought after of all flight records is for refueled, manned flight endurance. The current record of 64 days, 22 hours, and 19 minutes was set in 1958, by Robert Timm and John Cook. The story of this pair of Las Vegas pilots, and their record breaking flight is incredible, often funny, and always a little unbelievable. But to help put their story in the proper context, and give it a little additional weight, let’s start by defining flight endurance, and providing a little history.

Flight Endurance and the Early Years of Aviation

Flight endurance is defined as the longest amount of time an aircraft in a specific category can spend in continuous flight without landing. In manned flight endurance, flying can be handled by one pilot, though this is not the recommended method. The flying can be handled by multiple pilots, as long as all pilots remain in the aircraft for the duration of the flight. In the early days of aviation, flight endurance time was limited by how much fuel a plane could carry. But this was all about to change with the introduction of aerial refueling, something which would vastly increase the amount of time an airplane could stay in the air.

The first mid air refueling between two planes took place on June 27, 1923. The planes were Airco DH-4B Biplanes in the US Army Air Service. A mere two months later, the first refueled endurance record that beat the current un-refueled endurance record1 was set by three DH-4Bs, a receiving plane and two tankers. The receiving plane managed to stay aloft for more than 37 hours. During that time, it had 9 mid-air refuelings that pumped 687 gallons of gas, and 38 gallons of oil into its tanks. Over the years since that time, the refueled, manned endurance record has been broken on at least a dozen occasions. In 1929 alone, the record was broken and re-set five times!

In 1949, Bob Woodhouse and Woody Jongeward flew an Aeronca Sedan for 46 days and 9 hours before landing. These former Navy pilots were part of an effort to convince the government to reopen the Yuma Army Airfield, to help bolster the sagging Yuma economy. They were ultimately successful in their bid, also setting an impressive new endurance record that stood for almost a decade.

Fast forward 9 years to 1958. It’s two years after the release of the Cessna 172, which has become quite popular. Literally thousands have been built. Jim Heth and Bill Burkhart decide that this is just the plane to help them set a new flight endurance record. So, using a modified Cessna 172 called ‘The Old Scotchman‘, they took to the air in August 1958. 50 days (1200 hours) later, they landed, handily breaking the 1949 record. They were to enjoy this record for only a couple short months, however, as another group was finally ready to take flight in the deserts of Las Vegas.

Sin City and Flight Endurance

In 1956, Doc Bailey, an enterprising businessman, had built the first family oriented hotel and casino in Las Vegas, the 265 room ‘Hacienda‘. However, due to its (then) undesirable location at the far southern end of the strip, and its catering to families, locals, and those considered to be ‘low rollers’, the Hacienda had a reputation problem. It needs good publicity, and stat! Bailey tried many tactics, like hiring pretty women to hand out coupons to truckers, but he was soon convinced to engage in something much more ambitious.

Bailey, known for listening to and considering ideas no matter where they came from, was approached by one of his slot machine mechanics, Robert Timm. Timm, who at 240 lbs was described as a ‘bear’ of a man, was a WW2 bomber pilot, and an experienced aviator with a passion for flying. Timm convinced Doc that backing and publicizing an attempt to break the manned flight endurance world record was just the ticket. And with the name ‘Hacienda Hotel’ featured prominently on the side of the aircraft, it was sure to draw many eyes to the business.

To avoid the appearance of this flight merely being a publicity stunt for the hotel, Doc came up with an inspired idea. The flight would be a fundraiser, in support of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation. And anyone who wanted to guess how long the plane would stay in the air could send in their guess with a monetary contribution to the foundation. This would also qualify them for a chance to earn $10,000 if their guess was closest to the actual time the plane stayed in the air. Apparently, gambling is a-OK when it’s in support of a noble cause.

So, with Doc committed to backing the flight with $100,000, and Timm serving as the primary pilot, they needed two more things: a co-pilot, and an aircraft.

Modifying a Cessna 172 to Break the Flight Endurance Record

The aircraft came first. Tim reached out to his friend Irv Kuenzi, a mechanic at Alamo Aviation in Las Vegas. “He told me about this project he was going to get involved in and wanted to know if I’d be interested in helping him. I told him ‘sure.’” Kuenzi and Timm selected N9217B, a Cessna 172 with 1500 hours total time on the airframe. Kuenzi was familiar with this particular aircraft, and had already worked on it before. The plane’s avionics included a Narco Omnigator Mk II and a Mitchell autopilot, but Timm and Kuenzi spent almost a year modifying the Cessna 172 to be mission appropriate.

To start, they installed a 95 gallon Sorenson belly tank on the plane to supplement the 47 gallons of fuel the wing tanks could carry. They then outfitted this belly tank with an electric pump so it could transfer fuel to the airplane’s wing tanks. The planes oil lines were re-plumbed, allowing for the changing of engine oil and oil filters without shutting down the engine. The current interior furnishings, except for the pilot’s seat, were then completely removed. The co-pilot’s side door was also removed, and replaced with a folding, accordion style door. A small platform was designed that could be lowered out this door to provide more footing during refueling operations. In place of the co-pilot’s seat, they installed a four foot by four foot, four inch thick foam pad. And in the rear, they installed a small, stainless steel sink for the purpose of washing and shaving during the flight.

With these modifications in place, Timm and Kuenzi decided they also wanted to replace the plane’s current 450 hour-since-new engine with a brand new one. So Timm contacted Continental Motors (the manufacturer of the current six cylinder, 145 hp engine), explained to them his plan, and got them to agree to supply a new engine for the plane. Timm requested a special engine be built specifically for this attempt, and surprisingly, Continental agreed. It wasn’t until years later that Kuenzi found out exactly how they prepared the ‘special‘ engine. The sales manager for Continental came up with a simple solution, probably sensing that if the Hacienda was successful in breaking the flight endurance record using a special motor, everyone would soon be requesting special motors. The sales manager told a female co-worker to go down to the production line and pick the new 145 she liked the best. This ‘special‘ engine was then provided to Timm and Kuenzi.

Timm, also a certified airplane mechanic, had one additional modification he wanted to make to the airplane. He had Kuenzi install a primer-like system he had designed that would squirt alcohol into the combustion chamber of each of the engine’s six cylinders. It was Timm’s belief that this alcohol injection system would help prevent the buildup of carbon in the combustion chambers. Kuenzi did not agree, and fought Timm on this. However, he eventually conceded. Kuenzi removed the 450-hour-since-new engine from the Cessna 172, installed the brand new ‘special‘ engine from Continental, and hooked up Timm’s alcohol-injection system.

The First Attempts to Break the Flight Endurance Record

Finally, with all the modifications in place, it was time to take to the skies. The last thing Timm needed was a co-pilot. Sadly, the name of his first of two co-pilots seems to have been relegated to the dust-bin of history. I have been unable to find more than a few cursory sentences regarding this co-pilot’s role in the early attempts, and no identifying information. Timm and co-pilot A took to the skies twice in an attempt to break the endurance record, but each flight was cut short by mechanical problems.

Hoping that the third time would be a charm, they again took to the skies. Timm, who kept a diary during the flights, noted that at 4 AM one morning ‘the entire sky lit up.‘ Timm would later find out that he had witnessed one of the 57 above ground atomic bomb detonations set off during 1958 in the Nevada testing area2 65 miles to the northwest of Las Vegas. The third flight was also cut short by mechanical problems. This time, it was due to burned exhaust valves in the ‘special‘ engine.

None of these three flight lasted longer than 17 days. This was still enough time, however, for Timm to decide he was not getting along with co-pilot A. Timm dismissed this first co-pilot, and the search began for a new one. Timm was also becoming frustrated with the continued mechanical problems, and the delays they were causing. To add to his stress, Heth and Burkhart had just landed ‘The Old Scotchman,‘ breaking the previous record. They now would need at least 50 days in the air!

It Turns Out John Wayne Was at the Alamo

It turns out that Timm didn’t need to look very far to find his new co-pilot. He settled on John Wayne Cook, a lanky, single, 33 year old airplane mechanic with experience flying for the airlines. Cook was also employed at Alamo Aviation. As it turned out, Cook had also spent time working on N9217B, the Cessna 172 now dubbed ‘Hacienda‘. When Timm asked Cook if he’d join him on this fourth attempt, Cook simply replied ‘Sure, I’ll try.‘

While Timm searched for a new co-pilot, Kuenzi worked on the aircraft engine. He removed the damaged ‘special‘ engine, and reinstalled the old 450-hour-since-new engine. Acting on a hunch, and without telling Timm, Kuenzi also disconnected Timm’s alcohol-injection system. He rerouted it so that the alcohol would now be pumped out the bottom of the lower cowling. This hunch turned out to be spot on, and the used engine ended up working for over 2,000 hours of operation (1,559 continuous hours) by the end of the flight.

Finally, it was time to try once more. With slightly less fanfare than Bailey desired (this was their fourth attempt, after all) on 4 December 1958, at 3:52 PM, Timm and Cook lifted off from McCarran Field in Las Vegas. They were operating the aircraft at well above the maximum takeoff weight, but they had been granted a waiver by the FAA, allowing them to operate the aircraft with an additional 350-400 pounds of weight. After take-off, Timm and Cook made a pass on the airfield to allow a chase car to paint white stripes on the aircraft’s tires. This was to ensure that Timm and Cook didn’t attempt to cheat and secretly land the plane at some remote airport when no one was looking.

Tim and Cook flew ‘Hacienda‘ close to the Las Vegas area for the first couple of days. They wanted to make sure they had worked out any bugs or problems. After they were satisfied with the Hacienda’s flying, they made their way south towards Blythe, which had lower and less mountainous terrain. They spent most of their time flying over the deserts in the Blythe, California and Yuma, Arizona areas. However, on occasion, they would venture farther west to Van Nuys or Los Angeles to take part in promotional radio and TV opportunities.

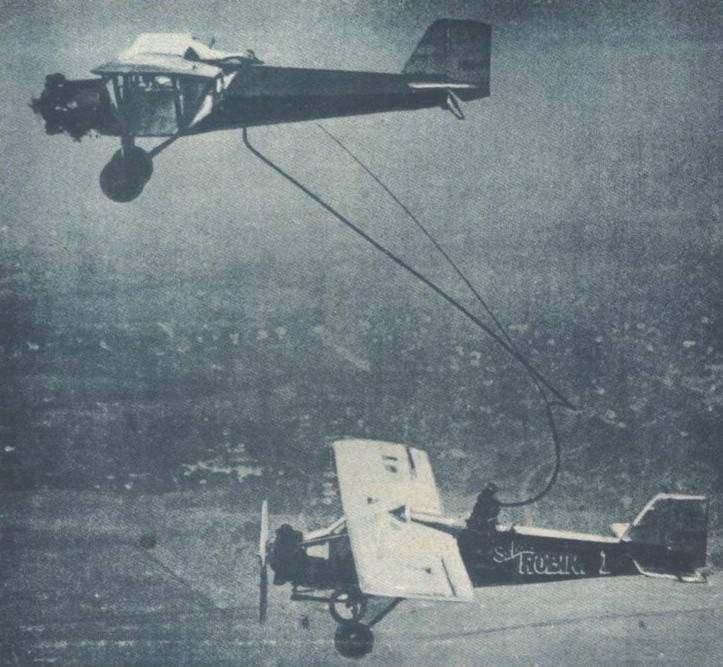

Keeping the Hacienda and its Pilots Fueled for the Flight Endurance Record

A Ford (as has been pointed out by a couple of astute, sharp eyed readers, the truck is actually a GMC) truck, graciously donated to the cause by Cashman Auto in Las Vegas, served as the primary support vehicle. The truck was outfitted with a fuel tank, pump, and other support items. Twice a day, the truck would rendezvous with the aircraft over a stretch of straight highway the Government had closed off. Hacienda would fly roughly 20 feet off the ground, and use an electric winch to lower a hook, and snag the refueling hose. Timm or Cook, standing on the platform that was lowered out the co-pilot’s door, would then insert the hose into the belly tank so the necessary fuel could be pumped up. It took roughly three minutes to fill the belly tank.

(Photo courtesy Howard W. Cannon Aviation Museum)

Sometimes, weather or other glitches would interrupt the schedule, and they’d quickly need to plan a new meeting time or location for refueling. They also had to deal with a non-functioning fuel pump. During these occasions, they would haul up a series of five gallon fuel cans using a rope. Over the course of the flight, this refueling process was repeated 128 times.

Oil, food, water for washing, towels, and other supplies were also passed up to the aircraft during these refueling runs. So, what exactly did the pilots eat? Doc Bailey instructed his chefs at the Hacienda that they were to feed the crew healthy meals, made only from the freshest and finest ingredients. These gourmet meals were prepared, but to get them up to the pilots in the plane, the meals had to be chopped up and stuffed into thermos jugs.

The Pilot’s Flight Endurance Routine

Timm and Cook worked out a schedule which had them flying in four hour shifts. When they weren’t flying, they would try to sleep as much as they could. And when not sleeping, they would attend to a variety of small chores to keep the plane flying, eat, flip through comics, perform what limited exercises they could, and brush their teethe and bathe. According to Cook’s diary, ‘We got a quart of bath water, a large towel, and soap every other day.‘ Hygienic activities in particular would prove occasionally awkward.

On one occasion, after finishing the refueling and other necessary chores related to flying, Timm preprared for his daily hygiene. He removed his clothes, lowered the platform out the co-pilot’s door, stepped out, and began brushing his teeth. Suddenly, Cook realized that they were a little low, and if the platform wasn’t pulled back into the plane, they would not be able to clear an upcoming ridge. He frantically yelled to Timm to get back in the plane, and pull in the platform. Later, Cook would tell about this experience, watching a bare naked 240 pound Timm struggle to pull in the platform with a toothbrush sticking out of the corner of his mouth and toothpaste streaming down his cheeks. They safely cleared the ridge, but this experience taught Timm and Cook to wait for flatter terrain to start their hygenic routines.

This also inevitably leads one to the question: how did they use the bathroom? Well, because the Cessna 172 doesn’t come standard with a toilet, and there was no room to install a permanent one, Timm and Cook had to rig their own system. This took the form of a folding camp toilet and plastic bags. Once they had been used, the plastic bags were then disposed of over unpopulated areas in the desert around Blythe. According to Mark Hall-Patton, the administrator of the Clark County Museum system in Las Vegas, “I once asked John’s widow if they handed down the waste during refueling runs. She said, ‘No. That’s why it’s so green around Blythe.’ ”

The first few weeks went by with fairly smooth sailing. On Christmas day, as they flew over the airfield, Timm and Cook dropped presents fitted with parachutes from the airplane, much to the delight of Timm’s two sons. Greg Timm, six years old at the time, recalls the incident fondly. “They flew by, in the airplane in the daytime, and tossed out of the airplane candy cane stockings with little parachutes. As they floated down my brother and I tried to snatch them before they hit the ground.”

Though the first few weeks passed without much incident, entries in Cook’s journal began to reflect the hardships of the flight. The lack of sustained physical activity, constant engine noise, and daily chores were wearing on both men. And though they rotated flying duties every four hours, it was difficult for either man to get much sleep, especially during the day. On January 9th, day thirty six of their flight, lack of sleep brought them dangerously close to a tragic end.

Timm was in the pilot seat, and dozed off at 2:55 AM as they flew over the Blythe airport. It was just minutes before Timm was scheduled to wake Cook to take over piloting. Timm dozed for just over an hour, waking up at 4 AM. The Mitchell autopilot had kept them in the air, and they were now flying due south through a canyon, halfway to Yuma. ‘I flew for two hours before I recognized any lights or the cities. I made a vow to myself that I would never tell John what had happened,’ Timm later disclosed to a reporter. It appears that Cook noticed, however, judging from this entry in his log:

“… it was 2:55 AM and he [Timm] was fighting sleeplessness. On auto pilot fell asleep 4000 FT over Blythe Airport found himself ½ way to Yuma Ariz 4000 ft. Very lucky. We must sleep more in the day time.”

Soaring By the Flight Endurance Record

A few days after the auto pilot saved their (probably fairly greasy) bacon, the generator on the Hacienda failed. This meant that 39 days into their trip, they were now without heat, lights, and the electric pump that transferred gas from the belly tank to the wing tanks. A wind generator was passed up and installed on one strut, but it provided very limited output. To combat the cold, Tim and Cook wrapped themselves in blankets. To push back the dark, they had flashlights and a string of Christmas lights powered by the wind generator. And in order to get gas from the belly tank to the wings, they now had to use a hand pump. Cook summed up these miserable new circumstances in his log:

“Hard to stay awake in dark place – can’t use radio – can’t use electric fuel pump. Pump all gasoline by hand, using minimum lights… Don’t realize how necessary this power until all of a sudden – sitting in the dark – no lights in panel to fly by – flashlight burning out – can’t see to fix the trouble if you could fix at all.”

Shortly after this, they encountered one of the things they had feared the most: a night refueling. It was mid-January, and there was no moon that night. Cook taped his flashlight onto the hook, and lowered it down to the fuel truck as Timm held position mere feet above. The ground crew, thankfully, had planned ahead. A pathfinder truck was deployed roughly 300 feet ahead of the fuel truck to give the crew a visual reference. Cook noted in his log that it was ‘as black a night as I’ve ever seen.‘

As they neared the fifty day mark, Timm and Cook began to carefully check each other’s work. They were determined not to let human error bring them down in their quest to break the flight endurance record. They carefully considered and discussed each new move and decision. Finally, on January 23rd, they broke the existing record set just months previous by Heth, Burkhart and ‘The Old Scotchman.’ Though they had accomplished their goal, and could finally land, they decided not to. Instead, they decided to keep flying for as long as they could, to ensure they held onto the record they had fought so hard to set.

“We had lost the generator, tachometer, autopilot, cabin heater, landing and taxi lights, belly tank fuel gauge, electrical fuel pump, and winch,” Cook wrote in his log. But in spite of these losses, they pressed on. By the beginning of February, the spark plugs and engine combustion chambers had become loaded with carbon. This greatly reduced the engine’s power, making it difficult to climb after refueling with a full load.

What Goes Up…

Finally, they decided to land on February 7th, 1959. Shortly before landing, the white paint on the tires was checked, and no scuff marks were found. They landed at McCarran Field after being in the air for 64 days, 22 hours, and 19 minutes. They had flown a little over 150,000 miles through the air, which was roughly equivalent to six times around the Earth. Timm and Cook were helped from the Hacienda, and Cook was quoted later as saying “There sure seemed to be a lot of fuss over a flight with one takeoff and one landing.” Their extra effort appears to have paid off, however, as their record still stands today.

After the flight, Timm returned to work at the Hacienda, and Cook continued a career as a pilot. The Hacienda (the aircraft) was displayed inside the Hacienda (the casino) for a few years, before being sold to a Canadian aviator. Before his death in 1978 (Cook died much later, in 1995), Timm would often reminisce about his days in the pilot’s seat, and expressed to his sons a desire to know what happened to N9217B.

Eventually, Steve Timm launched a search, and found the Cessna 172 on a farm in Carrot River, in Saskatchewan, Canada. He was able to bring it back to Las Vegas in 1988, where it eventually was acquired by the McCarran Aviation Heritage Museum3 and restored to its pre-flight condition. After spending some time at the museum, it was eventually moved to McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas, where it now hangs from the ceiling above the baggage claim area.

(Photo: Adolf Galland, CC2)

Some Final Thoughts

Steve Timm, years after the historic flight, had this to say: “Staying in the air for 65 days in a little plane the size of a Toyota, not landing. The noise, the danger, flying at night, all the various things that could have gone wrong that didn’t. My dad was in his early 30s and it almost killed him. My dad and John Cook were very lucky to have survived that, let alone break the record.” And while luck may indeed have played a large part, I feel that skill and no small amount of determination on the part of Timm and Cook also helped see the flight through to a record-setting end.

Some time after the flight, Cook was asked by a reporter if he would ever try to replicate the stunt, to which he replied: “Next time I feel in the mood to fly endurance, I’m going to lock myself in a garbage can with the vacuum cleaner running, and have Bob serve me T-bone steaks chopped up in a thermos bottle. That is, until my psychiatrist opens for business in the morning.”

Footnotes:

1 – As a sidenote, the un-refueled, manned record of 84 hours and 32 minutes, set in 1932, stood for over half a century. That record, however, was smashed in 1986 by Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeger (no relation to Chuck). They flew 9 days (216 hours) without stopping or refueling, circumnavigating the globe in the Rutan Voyager, a plane designed by Dick, Jeana, and Burt Rutan.

2 – As it turned out, this would be one of the last test detonations. The Government suspended above ground nuclear testing on October 28th, 1958.

3 – This museum is now called the ‘Howard W. Cannon Aviation Museum‘.

Comments

Post a Comment